Useful Daffodil Standards resources

Events and webinars

End of Life Care – Compassion in the workplace

This webinar covers talks about a whole system approach to compassion in relation to people, places and processes. It explores how to deal with the loss of the colleague, including suicide, sudden loss and long term illness. It covers Daffodil Standard 8 - for practices interested in assessing and improving your compassionate culture and leadership.

Advance Care Planning, DNACPR & What Matters Most Conversations

The event is chaired by Dr Catherine Millington Sanders. She is the RCGP and Marie Curie National Clinical End of Life Care Champion. Professor Mark Taubert, Consultant in Palliative Medicine & Honorary Professor Cardiff University, School of Medicine, is a guest expert speaker. He is joined by guest expert speaker Catherine Baldock, Clinical Lead for ReSPECT, Resuscitation Council UK.

End of Life Care - Symptom control and care of the dying

This webinar covers symptom control and care of the dying. The event is chaired by Dr Catherine Millington Sanders, RCGP / Marie Curie National Clinical End of Life Care Champion Guest expert speakers are Dr Iain Lawrie, Consultant in Palliative Medicine at North Manchester General Hospital, and Dr Sarah Holmes, UK Medical Director, Marie Curie.

End of Life Care – Early Identification & DNACPR learning

This webinar covers Early Identification & DNACPR learning. The event is chaired by Dr Catherine Millington Sanders, RCGP and Marie Curie National Clinical End of Life Care Champion.

Guest expert speakers are:

- Dr Rosie Benneyworth, Chief Inspector of Primary Medical Services and Integrated Care at CQC

- Dr Nazmul Hussain, GP Trainer, Newham Clinical Director & CCG clinical lead EOL/Frailty

- Dr Andrew Fletcher, Medical Director, St Catherine's Hospice, Consultant in Palliative Medicine, Lancashire Teaching Hospital NHS Trust

- Dr Lyndsey Williams, NWL EOLC clinical lead, Macmillan GP Brent CCG

- Dr Paul Baughan, GP in Clackmannanshire and Professional Adviser to the Scottish Government, CMO directorate.

Quality Improvement Criteria Guidance

The Daffodil Standards are not meant to be 'perfectionistic', instead they allow all staff to start and improve at their own individual pace and for a practice to understand and build on their strategy to reliably support all patients with advanced serious illness and end of life care needs, as a journey. The aim is to support a practice to always be ready to ask questions, find new solutions and continue to make small steps – testing change, removing problems/ inefficiencies and refining practice. Details of some of these tools that you could use can be found in the QI guidance below.

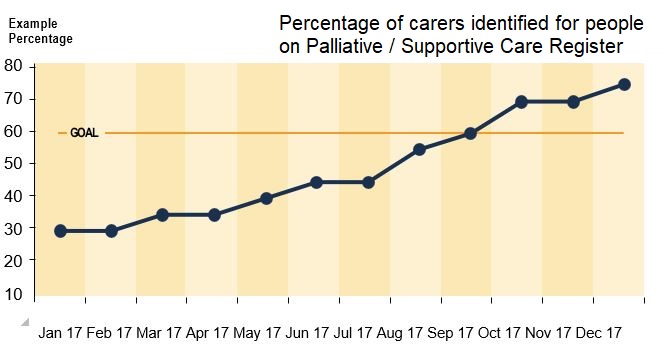

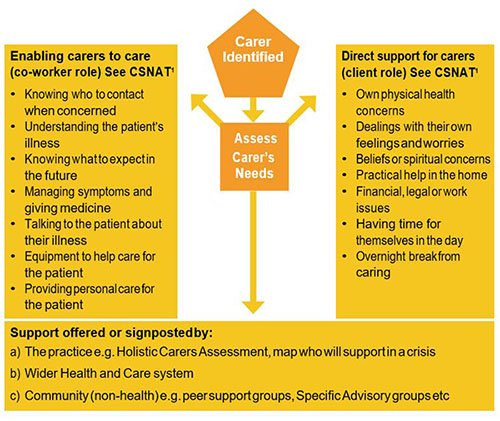

Monthly recording of percentage of carers identified for patients on Palliative Care/ Supportive Care Register. Displayed on a line graph with an increasing objective to reach around 60-90% of Supportive Care Register patients, or a % that is aligned with their population.

In addition to carer identification, other continuous improvement goals may be:

- Increasing carer assessments

- Increasing carer support offered/ signposted by the practice

Guidance

Estimates suggest that between 60-90% of people in the last year of life are likely to have an informal carer e.g. spouse/ partner, sibling, son/daughter, neighbour /friend. A very good practice would be anticipating at least 60%.

Record the percentage of the people who died on the palliative/ supportive care register AND the percentage of these who had informal care-giver details recorded and coded, on the last day of each month. Plot the percentages on a line graph with the goal e.g. 60% drawn as a line across the graph. There may be reasons related to your practice demographics where a lower goal can be justified. Display the graph in a prominent position in the practice where all involved in creating the list can see the effect of their work.

This involves considering your practice team in terms of its 'Strengths', 'Weaknesses', 'Opportunities' and 'Threats'. This exercise is very useful in bringing together individuals with different viewpoints, so that they can air their opinions and concerns and at the same time hear why others are excited by care for people affected by Advanced Serious Illness and End of Life Care. With a focus on safe and compassionate care for people affected by Advanced Serious Illness and End of Life Care, ask the group to answer the following question and write their response down, one per post-it note.

In this aspect of care …

- What are our strengths?

- What are our weaknesses?

- What opportunities can we see?

- What threats can we see?

Then collate the post-it notes on a flip chart divided into 4 quadrants, asking for clarification about what is written if necessary, so all views are heard.

The team can then build on the strengths and opportunities, address the weakness and avoid the threats.

Monthly recording of percentage of patients on the practice list that is on Palliative / Supporting Care Register with Advanced Serious Illness and EOLC. Displayed on a line graph, considering a number (or %) that is aligned with their population. Defined practice population (or %) = number of deaths in the last 12 months / total practice population.

Guidance

The national average of people dying each year is approximately 1%, but this can vary between individual practices due to differences in the demographics of the practice population. Practices can use the number of deaths reported in the previous year to calculate their own figure and use this to assess how well they are identifying patients who would benefit from end of life care. Estimates suggest that between 60-70% of deaths may be anticipated, but this can be challenging to achieve in practice. A very good practice would be anticipating approximately 60% of deaths.

Record the percentage of the people who died AND who had been identified on the supportive care register on the last day of each month. Plot the percentages on a line graph with the goal e.g. 60% drawn as a line across the graph. There may be reasons related to your practice demographics where a lower goal can be justified. Display the graph in a prominent position in the practice where all involved in creating the list can see the effect of their work.

Incorporate the use of MDT Template (XLSX file, 307 KB) to support better and consistent decision-making and discussions at MDTs for patients and carers. This is a key part of achieving Level 1 of the Daffodil Standards.

Use the MDT template to monitor or retrospective audit template (XLSX file, 305 KB) to consider all deaths and any learning (for people identified on the Palliative Care / Supportive Care Register and people who died but were not identified).

If reflected on regularly at each MDT (e.g. monthly), this naturally helps the practice a) plan care and support for those identified and b) learn from deaths. In addition, the template forms the basis of a regular (e.g. annually) practice Retrospective Death Audit (to cover an agreed time) and action taken where outcomes achieved do not meet the practice accepted standards.

Consider continuous monitoring of template criteria e.g. Personalised / Anticipatory Care & Support Plan recorded, which are plotted on a line graph monthly. Consider National Information Standard for minimum EOLC dataset.

Consider reviewing current and agree future consistent EOLC codes, aligned to MDT template/audit column headings, to be recommended for use by all staff. This forms your monitoring dataset, across key Daffodil Standards. Monitor use and repeat review after agreed period of time.

Guidance

1. Annual retrospective death audit.

This annual retrospective death audit may include fewer criteria than the first audit included in the evidence for the standards. You could omit criteria where there was no room for improvement.

The following are standard headings for a clinical audit report, with tips on how to define and fulfill each section. This process satisfies the requirements of General Medical Council revalidation.

Step 1: Title

A retrospective death audit.

Step 2: Reason for the audit

To assess the standard of care the practice is providing for patients with advanced serious illness and at the end of their life.Step 3: Criteria or criterion to be measured

Keep your audit simple and effective by choosing just a small number of criteria. Each criterion should pose easy ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions so you will know if it has been met. Here is Example Retrospective Death Audit (XLSX file, 305 KB), an Excel collection template with example criteria, aligned to each Daffodil Standard.

Step 4: Standards set

In audit the RCGP defines a ‘standard’ as the level of performance achieved and expressed as a percentage. It can be derived from external sources, such as audits that have been done elsewhere, or determined internally from discussion with clinicians in the practice. The standard should be realistic rather than idealistic so try and avoid a standard of 100%.

Step 5: Preparation and planning

All patients with ASI or EOLC who died and were on the register should be included in the audit. Decide how you will record your results, whether by using a software package or a simple paper checklist that records Yes/ No/ Not applicable.

Step 6: Results and date of collection 1

Presenting the results in a table makes them easier to understand.

Table 1: Template for clinical audit results (collection one).

| Criterion | Number sampled | Percentage achievement | Standard set |

|---|---|---|---|

Step 7: Description of change(s) implemented

From your results it will be easy to see whether or not your criterion or criteria have been met. Based on this, a decision can be taken on the changes to be made. This may be done once results have been presented to others to gain their opinion, especially if the change(s) will affect other team members. Sharing your audit results with the whole practice team will increase the likelihood of improvements being sustained.

Step 8: Results and date of data collection 2

This can be presented in an extension of the previous table, with an additional column for the second data collection

Figure 2: Template for clinical audit results (collection two).

| Criterion | Number sampled (first data collection) | Percentage achievement (first data collection) | Number sampled (second data collection) | Percentage achievement (second data collection) | Standard set |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Step 9: Reflections

Present the conclusions of your audit project including any lessons learned, any further steps of change required and when the audit will be repeated. Even when your target standard has been reached the audit should be repeated to ensure the change is sustained.

2. Regular monitoring

Some of the criteria monitoring (practice choice) should be plotted monthly on a line graph. This is best done as a percentage of all the sampled patients. Once data for a whole year has been collected then a cumulative line graph should be used. The standard percentage should be drawn as a line on the graph. In this, the percentage for 12 months is used. Every time a new month is added, the month at the start of the collection period is excluded and the new month is added to the rest of the 11-month figures. So, if your collection of figures commenced in April 2021 then when you have the figures for April 2022, you omit those for April 2021. By doing this it helps copes with small numbers of patients dying every month in a practice.

Every quarter the percentage of emergency admissions for those on the register should be recorded and plotted. As in the previous monitoring one a year’s figures have been collected then a cumulative line graph could be plotted. Trends can be identified on the graph, discussed and any further action planned.

The practice has identified areas for improvement from their process map (see 5.1b). They then use the 3 questions from the Model for Improvement, which are:

- What are we trying to accomplish?

- How will we know if a change has made an improvement?

- What changes can we make that will result in an improvement? One of these changes at a time are taken into a Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle.

Guidance

Often it is not easy to find an effective solution straight from the process map. Hence you can stop the process map tool after you have identified the areas for improvement. You then take one of these areas into the Model for Improvement.

- What are we trying to accomplish?

- How will we know that a change is an improvement?

- What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

Question 1: What are we trying to accomplish?

This needs to be specific and include 'by how much?' and 'by when?'

Question 2: How will we know if a change has been an improvement?

Decide what you are going to measure so that you know whether your ideas for change are working.

Question 3: What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

To answer this question, consider all of the ideas for change. This is best done by asking for all team members to suggest a change in a meeting.

Then one of these changes are taken into a PDSA cycle.

Plan

Planning will include identifying who will be responsible for the change; when it will be carried out; over what timescale; and how the measurement will be conducted. Involve all stakeholders in the process and do persuade any reluctant team members to participate. Consider how you might look out for the unexpected.

Do

First collect your baseline data to monitor the existing state of play. You might do this as part of 'planning' or 'doing'. Ensure that all individuals who are conducting the measurements understand what data is being collected and how to collect it. After sufficient time, continue to collect the data but introduce the agreed change. If you are considering implementing several changes, you would usually introduce one change at a time so that the effect of each can be measured. By introducing only a small change you are likely to encounter less resistance, and, if unsuccessful, adaptions can be made more quickly. The scale at which you test your change should also be kept small at first. Any problems encountered, and any unexpected consequences, can be recorded as implementation progresses.

Study

The success or failure of the change is assessed at this stage, both quantitatively (by looking at the data collected) and qualitatively (by discussing how everyone experienced the change). You should compare the results with the predictions you made and document any learning, including a record of the reasons for success or failure. Not all changes result in improvement, but learning can always be gleaned.

Act

In this stage, decide whether you just need to adapt what you have tried or whether you might try something completely new instead.

The online Rubik's Cube solver programme will help you find the solution for your unsolved puzzle.

Implementation of 5 priorities of care across all deaths and action taken where outcomes achieved do not meet the practice accepted standards. Continuous monitoring of these criteria e.g. pain and symptoms assessed regularly in last days of life.

For example, consider if the practice has a reliable system in place to assess with the patient and those important to them the 5 priorities of care AND document that the 5 priorities of care have been met, where possible.Guidance

Guidance on audit can be found in the guidance for QI 4. The 5 priorities of care are:- Recognise: The possibility that a person may die within the coming days and hours is recognised and communicated clearly, decisions about care are made in accordance with the person’s needs and wishes, and these are reviewed and revised regularly.

- Communicate: Sensitive communication takes place between staff and the person who is dying and those important to them. Conversations are appropriately documented.

- Involve: The dying person, and those identified as important to them, are involved in decisions about treatment and care.

- Support: The people important to the dying person are listened to and their needs are respected.

- Plan and do: Care is tailored to the individual and delivered with compassion – with an individual care plan in place.

Not all these priorities are well recorded in the records but you should encourage future recording. Choose a priority that is recorded and where you think the practice has room for improvement. All deaths on the register should be included. You may wish to do the audit quarterly collecting the data retrospectively or prospectively. You should monitor this data over several quarters.

Regular audit of support offered to the bereaved for example, documented contact with the bereaved, support information given.

Guidance

Guidance on audit can be found in the guidance for QI 4.

You should use criteria that are derived from your practice policy on support of the bereaved. Examples are:

- An information leaflet is provided to the bereaved

- A call to offer condolences either by phone, written or visit is made to the bereaved

- With agreement with person, ‘carer’ code is removed and bereavement coded, as appropriate

- A quarterly audit done over several quarters would be appropriate.

In order that lessons can be learned from the experience of advanced serious illness, EOLC, caring responsibilities, death and bereavement. Lessons can be shared with the relevant people.

Consider practice staff/ patients/ carers feedback and how the practice is meeting the end of life/ bereavement care needs, and show how any information provided is used to help improve care and support by achieving:

- 2-5 family/care-giver or patient interviews e.g. semi-structured discussion, using an agreed template or annual carer survey relevant to EOLC needs.

- Staff feedback to support the QI planning e.g. survey, debriefs, SEAs

- MDT feedback to support the QI planning e.g. survey, discussion at MDT

- Annual evaluation of compassionate organisational culture

Guidance on SEAs as an example

SEA meetings have been shown to be a valuable tool in learning. They can form part of a doctor's evidence for appraisal.

SEA process enables the following questions to be answered:

- What happened and why?

- What was the impact on those involved (patient, carer, family, GP, practice)?

- How could things have been different?

- What can we learn from what happened?

- What needs to change?

Enhanced significant event analysis is a further improvement to the existing SEA structure. A 'human factors' approach was taken in a NHS Education for Scotland (NES) pilot funded by the Health Foundation Shine programme. It considers contributory factors to an event and their interactions under headings of People factors, Activity factors and Environment factors. Human factors addresses problems by modifying the design of the system to better aid people: to understand and limit conditions in the system that predispose an individual to make an error and to reduce the risk of errors leading to harm. Further details on this study can be found on the NHS Education for Scotland website.

The evaluation of compassionate organisational culture can be done through discussion at a practice meeting. In this discussion you are concentrating on how the practice team are supported. Tools such as SWOT analysis (see guidance for QI 1) or a celebrations/frustrations charts can be used. In the latter, two flipchart sheets are used. One is headed celebrations and the other frustrations. Ask the team what they think is good about the practice's compassionate culture and list all comments under "celebrations". They can write the item on a post-it and stick it onto the sheet. Then move onto frustrations, reminding participants that this should not be criticism of a person but rather of systems and processes. Remember to steer the group to completing the celebrations before moving to frustrations. Actions can be considered to overcome the frustrations.Multi-professional mini-modules:

- ‘Practical steps to assessing your baseline and developing a compassionate workplace culture and leadership in general practice (0.5 CPD points)’

- Podcast, ‘Developing a compassionate workplace culture and leadership in general practice – learning from a GP pilot site (0.5 CPD points)

- Awareness of national resources for instance from Compassionate Cymru

Reflective Group Learning

Reflection exercises as a practice

Figure: Kolb's learning cycle.

It is normal for practice staff to have different experiences and beliefs when dealing with patients and carers at the practice. This is often informed by their personal life experiences. Evidence shows that learning is richer when we are able to share our different experiences. This reflection and sharing helps promote the culture of learning and continuous quality improvement within the practice and stops the achievement of the standards being a simple tick box exercise. Ideally this reflection can be done at a group meeting.

Ground rules for a group meeting

To state the ground rules at the start of the exercise to create a safe environment for discussion:

- Agree as a group the time available for discussion and who will lead the facilitation

- Everyone’s opinion and beliefs are valid and to be respected

- Emphasise this is a learning discussion

- Confidentiality

- Remember that discussing these sensitive issues can be difficult for anyone, particularly if it brings up similar personal memories. So offer people the ability to stop being involved in the discussion and leave the room if a person finds the discussion too emotionally difficult

- Remember another function of the group is to support each other

- Make sure there is a named lead (either in or not in the group) who is aware of the session and available to discuss and debrief/offer support to any member of the team if distressing emotions are uncovered. This may be during the session or a period of time afterwards.

Record: Those attended, apologies, and date of meeting.

The aim

- To enable clear leadership and a culture of learning and quality improvement within the practice

- For each staff member to tap into their own experiences of handling patients and carers affected by advanced serious illness and end of life care.

Principles

- Select a patient where learning can be achieved

- "No blame" culture

- Encourage reflection

- Make recommendations for improvement

- Re-assess actions or learning at a later stage

Discussion

Using a significant event analysis format where the culture of the practice is conducive to reflection has been shown to be effective in providing support and learning to the practice team.

Task

- Consider the leadership model the practice wants to develop to enable high quality care for people affected by advanced serious illness and end of life.

- Who is best placed (for example, skills, time, desire) to be the clinical and administration lead for the Daffodil Standards?

- How will the practice support them? Time, training, coaching, development support to staff etc

- How much quality improvement experience had they got? How can they ensure they have minimum baseline knowledge? For example, modular learning: West of England Academic Health Science Network Education Pathway or NHS Scotland. The Life Science Hub Wales provides quality improvement learning and tools, as well as advice via Improvement Cymru. End of life care leads can also consider registering their quality improvement ideas as NHS Wales Bevan Commission Exemplar projects. Is there a GP network available to share practice learning?

- How will they know they are making a difference/ improvement?

- Each person to think about a specific patient or carer you have handled who was/is affected by advanced serious illness and/or end of life needs.

- Go round the group and ask people to say which patient they are thinking of. Agree a patient to discuss.

- Consider tasks undertaken by members of the team when caring for people affected end of life

- Ask people to volunteer A FEW WORDS ONLY what was most rewarding about being involved in their care.

- Discuss the following questions as a group (and someone take notes on the key points):

- What happened with the patient initially?

- What happened with the patient initially?

- What happened subsequently?

- How did the person present to or get noticed by you?

- Who else in the practice knew them?

- What were their potential needs – health, psychosocial, spiritual, practical and other? Explore different people's attitudes, beliefs and experiences

- What worked well /made a difference? – for the patient, for you, other staff, for the practice?

- What was the learning for you?

- Was there learning for the practice an external to the practice

- What will you do differently in the future?

- How and when will you address learning for you, the practice, and external to the practice?

- Set a review date.

Informing part of the evidence on Standard 1

- Helps identify those involved in ASI and EOLC

- May identify roles

- Can identify learning needs

- Case history recorded

- May involve patient/carer

- Demonstrates sensitive communication

- Can form part of SWOT analysis

QI 1: Continuous Improvement

Yearly SWOT (Strengths / Weaknesses / Opportunities / Threats) analysis of the practice’s ability to provide high quality, safe and compassionate care for people affected by Advanced Serious Illness, EOLC and bereavement.

Record: Those attended, apologies, and date of meeting.

The aim

To continuously develop a 'Palliative Supporting Care Register' for patients and carers affected by advanced serious illness, frailty and end of life care.Principles

A supportive care register should have recorded a minimum dataset.

Also, see Retrospective Death Audit dataset (DOCX file, 68 KB) and Retrospective Death Audit Template (XLSX file, 305 KB).

Discussion

The number on the Supportive Care Register should be maximised and early identification of patients is desirable. This should reflect the number of expected deaths that a practice would handle each year.

A simple formula to estimate this is:- Number of expected deaths each year = Number of deaths (previous year) / Practice population (previous year) x 0.75 (proportion of expected deaths)

Task

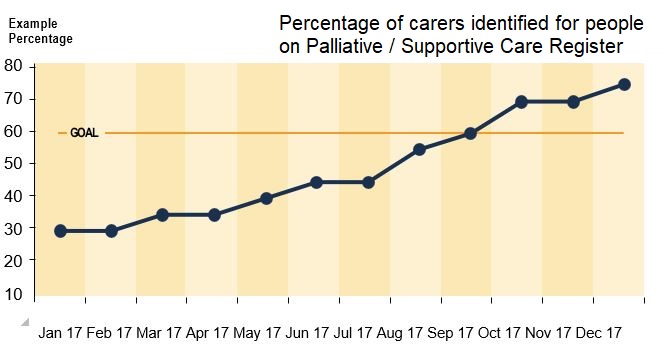

- For practice staff (clinical and non-clinical) to understand an agreed, clear protocol to identify patients and carers affected by advanced serious illness and end of life needs.

- Consider who at the practice is involved/has contact with patients and carers affected by advanced serious illness, frailty and/or end of life needs.

- Consider ALL staff opportunities for early identification, as part of their usual role. The majority of people are likely to be identified using common sense, robust processes and clinical judgment. There will be crossover between roles, but some general examples are given below to stimulate discussion.

- Confirm how identified patients and carers will be collated and coded on a 'Palliative Supportive Care Register' (name of register can be decided by the practice).

- Confirm how identified patients and carers will be highlighted /flagged to ALL practice staff to enable rapid access.

Discuss the following questions as a group (and someone take notes on the key points):

- What happens currently to identify patients and carers early?

- What works well and what could be improved? Each person to discuss from their perspective. o Explore different people's attitudes, beliefs and experiences – ensure lone voices and concerns are heard.

- Each person (may help to group roles) to agree what they will commit to trialling within their role to support early identification.

- Set a timeline for the trial and for the review date.

- Review date to consider shared learning from trials, what happened, what worked well, what was less effective and what should be stopped (that is, it did not work), adapted or continued.

- Set next review date.

Informing part of the evidence on Standard 2

- Help create a protocol for identifying patients and carers, with ASI, frailty and EOLC needs

- Identify how to seamlessly code and record patients and carers onto the register

- Staff aware of the identification protocol, register and their role

- Components of the register known to all

- Share recording of percentage on list

QI 2: Continuous Improvement

- Monthly recording of percentage of patients on practice list that is on Palliative Care/ Supportive Care Register. Displayed on a line graph, considering a number (or %) that is aligned with their population. Defined practice population (or %) = number of deaths in the last 12 months / total practice population

- Evidence base: 60-70% of people have an expected death and planning can support their needs with early identification of their needs

Record: Those attended, apologies, and date of meeting.

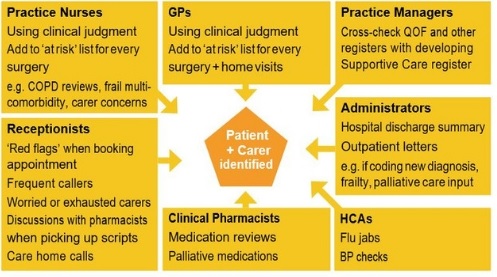

The aim

- To develop a clear understanding of how the practice supports carers before and after death

- To continuously develop processes to improve support to carers

- To continue to develop the quality of care and support offered to carers

Principles

Task

- Consider who at the practice is involved/has contact with and carers supporting a person affected by advanced serious illness and/or end of life needs.

- Discuss the following questions as a group (and someone take notes on the key points):

- Each member of the team to offer suggestions of how the practice currently supports carers?

- How do different members of the team pick up and/or assess Carer's Needs? Consider both co-worker and client roles.

- What works well and what could be improved? Each person to discuss from their perspective.

- What gaps are there to offer holistic carers assessments and to support carers needs within the practice?

- What could be trialled to help improve:

a) the processes and

b) quality of care for carers?

- Each person (may help to group within roles) to agree what they will commit to trialing within their role to support this improvement.

- Set a timeline for the trial and for the review date.

- Review date to consider shared learning from trials, what happened, what worked well, what was less effective and what should be stopped (i.e. it did not work), adapted or continued.

- Set next review date.

Informing part of the evidence on Standard 3

- Holistic carers assessment

- Create criteria for audit

QI 3: Continuous Improvement

Monthly recording of percentage of carers identified for patients on Palliative Care/ Supportive Care Register. Displayed on a line graph with an increasing objective to reach around 60-90% of Supportive Care Register patients, or a % that is aligned with their population.

Evidence base: 60-90% of people in the last year of life are likely to have an informal carer e.g. spouse / partner, sibling, son / daughter, neighbour / friend.

References

- The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) intervention

- Ewing G and Grande GE (2018). Providing person- centred assessment and support for family carers towards the end of life: 10 recommendations for achieving organisational change. Hospice UK. London

Record: Those attended, apologies, and date of meeting.

The aim

- To confirm effective MDT structure (form)

- To develop a robust MDT process (function) to review, make decisions, plan and support the health (and non-health) needs of patients with advanced serious illness and end of life care.

Principles

A MDT requires:

- Representation from relevant disciplines

- Leadership

- Terms of reference

- Referral process

- Co-ordination and administration

- Access to data

- Outcomes monitored

- To be patient centred

- Purpose defined

- Specific Measurable Achievable Realistic Time based (SMART) goals

Example headings of terms of reference for MDT meeting

- Aim of meeting

- Objectives of the meeting

- Membership - Core/ Non-Core

- Attendance

- Time and venue of meetings

- Chair arrangements

- Notification

- Agenda

- Process to enable patients / carers are discussed, e.g. how patients on Supportive Care Register are raised for discussion

- Confidentiality

- Meeting documentation

- Communication with patients and families

- Review period for Terms of Reference

Discussion

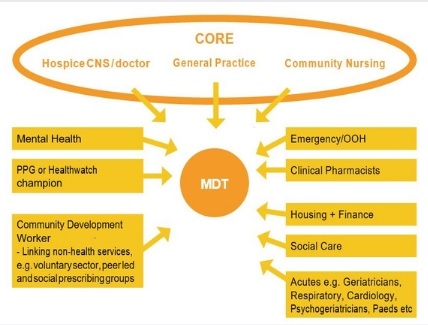

For professionals across different settings to make time to attend and contribute to a MDT, people fundamentally have to believe their input is making a difference. So if you have a combined MDT of different functions, then to avoid disengaging colleagues, it is advisable to invite the relevant team members to a distinct MDT for patients identified and on the practice 'Supportive Care Register'(name to be decided by the practice) – reviewing Advanced Serious Illness /EOLC.

This aims to give guidance on a framework to General Practice to establish high-performing MDTs.Each practice will be unique and this does not suggest a 'one size fits all' approach and simply aims to offer guidance on a structured approach to align patient-centred care with local service delivery.

Once set up, it is easy for MDT to stagnate and not necessarily achieve the outcomes desired. Therefore, it is important to agree the right / necessary people to have in the room, agree as a team the desired outcomes and to regularly check-in with colleagues if you as a team feel you are achieving those goals.Depending on the skill mix and collaboration between GP networks (groups of practices working together at scale), it is possible to consider MDTs at scale and the same framework can be used.

Task

Discuss the following questions as a group (and someone take notes on the key points)

- Define the MDT structure (form) of your MDT

- The Team

Core team? Who from the practice? Who from outside the practice? Suggested minimum: GP, hospice and community nursing representatives. Examples of wider representation, including virtual input and at scale, below:

- Leadership: Who chairs the meeting? Rotating chairs?

- Attendance: Discuss how often does (and practically can) the MDT meet? Chair to decide if quorate and sufficient representation to hold MDT

- Governance: Is there a basic Terms of Reference for the MDT? Record of attendance for each meeting?

Meeting operation

Selection

- How are referrals received?

- Does your MDT use an electronic or paper-based pro forma/template with required data fields, to enable quality assurance? Daffodil Standards Retrospective Death Audit (XLSX file, 307 KB)

- Who can refer in? Professionals, patients, carers?

- How do referrals relate to identified patients on the practice's 'Supportive Care Register'?

- How are referrals prioritised? For example, example of GSF Needs based coding: Blue (A) Year Plus prognosis Green (B) Months prognosis Amber

(C) Weeks prognosis Red (D) Days prognosis OR coding based on priority of need for example, Red (Urgent) /Amber (Deteriorating) / Green (Stable) - How are medical needs considered? How are non-medical needs considered?

- What community response is available in your locality?

Coordination and administration

- Who receives, reviews for completeness and collates the referrals?

- Who records the outcomes from MDT discussion?

- How is information coordinated back to relevant GP(s)?

- How is key information shared with other providers and patients in and out of hours?

- Who completes MDT template data set to enable audit and reflection?

- Is conference technology available, for team members to call in, if required?

Data Collection and monitoring

- How does the MDT template data set align with national and local datasets?

- How is key information coded? See example. Are outcomes documented in real-time?

- How is data used to monitor and audit patient pathways locally and at scale?

- Consider how will you know and monitor if the MDT is working well or not?

- How regularly are MDTs reviewed to consider their effectiveness?

- How does the practice understand what data to collect in order to measure your impact and enable business cases for further development?

- How does the MDT routinely review and learn from deaths – expected and unexpected?

- What criteria do you use to consider and report a death as an SEA?

Patient-centred care

- Role of the patient, for example, how are patients informed they are discussed at the MDT? For example, written or verbal information

- How are MDT recommendations/ information communicated back to the patient and those important to them?

- If the patient does not have capacity, is 'best interest' consent documented to enable MDT discussion?

- How is each patient involved in the decisions about their treatment goals, non-medical goals and care plan?

- How do you measure patient experience for care received by patients with advanced serious illness and end of life care needs?

Agree the MDT purpose and function

The purpose could be: information-sharing; decision-making; education; peer support.

- Clarify with the team the purpose of the MDT and how it will help plan seamless, coordinated care for people identified with advanced serious illness and end of life care needs, on the 'Palliative Supportive Care Register' (name to be decided by the practice).

- Set clear, SMART goals/outcomes for the MDT. Discuss with the team:

- Areas of diversity in beliefs about purpose of the MDT.

- How does the MDT consider goals of family and carers – at diagnosis,deterioration/crisis, nearing death and after death.

- How does the team enable efficient decision-making and information-sharing to align with patient-centred goals?

- How does the MDT report risk or changes within 'the whole system'?

- How does the MDT consider inequalities and strive to improve equitable care for their entire population? CQC thematic EOLC review.

3. Daffodil Standards Retrospective Death Audit (XLSX file, 307 KB) Each month (or between MDTs), consider patients who died at the MDT.

- Is there a robust and timely way for all deaths to be documented, in a way that is accessible to all practice and MDT staff?

- Were they identified and on the practice 'Supportive Care Register' (name to be determined by the practice)?

- Were they expected or unexpected deaths?

- For unexpected deaths in the community

- What lessons can be learned from the care and deaths for the patient and for those important to them? (use each standard to consider factors)

- In line with CQC national review, is there a robust system for the practice to assess and identify for serious incidents such as preventable deaths? What process and criteria do the practice follow to report in a timely manner serious incidents of preventable deaths? Consider complementing Serious Incident Framework. Is there a CCG/ locality/ health board wide agreed process?

- Is there a system in place to share learning across the system?

- How is information shared with patients and those important to them? How are they involved?

- How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

4. For expected deaths in the community:

- Were the patient and those important to them identified on the practice 'Palliative Supportive Care Register'?

- Did they have a Personalised Care and Support Plan? Were Five Priorities of Care for the dying met?

- ID the carer/ those important to the deceased receive an agreed level of after death bereavement care, set by the practice?

- Are there any opportunities for learning?

- How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

5. How do you collate these mortality reviews to form an annual analysis of deaths for the practice? How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

Informing part of the evidence on standard

- Agree form and structure of MDT meetings

- Mechanism for review of patients on register

QI 4: Continuous Improvement

Incorporate the use of MDT template to support better and consistent decision-making and discussions at MDTs for patients and carers. This is a key part of achieving Level 1 of the Daffodil Standards.

Use the MDT template (XSLX file, 307 KB) to monitor or retrospective audit template (XSLX file, 305 KB) to consider all deaths and any learning (for people identified on the Palliative Care/ Supportive Care Register and people who died but were not identified).

If reflected on regularly at each MDT (e.g. monthly), this naturally helps the practice a) plan care and support for those identified and b) learn from deaths. In addition, the template forms the basis of a regular (e.g. annually) practice Retrospective Death Audit (to cover an agreed time) and action taken where outcomes achieved do not meet the practice accepted standards.

Evidence base: builds on National Information Standard for minimum EOLC dataset.

Record: Those attended, apologies, and date of meeting.

The aim

- For the practice to consider how best to manage care planning.

- To routinely offer/enable timely and accessible conversations to facilitate holistic, personalised care and support planning1,2,3 for people with advanced serious illness and end of life care needs, and where relevant to those important to them.

This includes:

- Treatment escalation plan.

- Advance Care Plan.

- Links to support within the community: map who is available to support the patient and family/carer in a crisis and also to support living well – considering anxiety, depression, loneliness and social isolation.

Examples

- Letter to patient – my life plan (invite) (PDF file, 296 KB)

- Letter to patient – my life plan (new) (PDF file, 180 KB)

- Letter to patient – my life plan (review invite) (PDF file, 180 KB)

- Letter to patient – my life plan (updated) (PDF file, 179 KB)

- Managed MDT (PDF file, 191 KB)

- My life plan – first consultation (PDF file, 466 KB)

- Treatment escalation plan (PDF file, 243 KB)

Principles

- Ask permission to discuss planning - do not force

- Go at the patient's own pace

- Involve family, carers and those important to the patient

- Ensure information is discussed and accessible in a way the patient can understand

- Gain shared understanding of patient's current and potential future health and care

- Gain shared understanding of patient's goals of treatment, care and support: a) general care, as planned, b) in a crisis, more or less sudden significant deterioration, c) legal documentation, e.g. DNACPR, ADRT, LPA

- Shared understanding of who is in the patient and carer's support network and how they may help support with non-medical needs

- Record agreed decisions and code, and flag to practice staff that a plan is available

- Share the plan with: a) the patient, and those important to them; b) key professionals, in and out of hours

- Agree review time

Discussion

Personalised care and support plans (PSCP) aim to promote patient-centred, informed care and a structure to enable compassionate discussions about medical and non-medical goals of care, empowering choice with the right to consent to or refuse treatment and care offered. It is sensible for plans to consider possible future emergencies, incorporating if they are unable to make or express choices. Where relevant, discussions should involve family, carers and those important to the patient.

Ideally, personalised care and support planning discussions occur when a patient’s condition is stable, in anticipation of crisis, deterioration and dying. However, there may also be an opportunity to start the process of Personalised Care and Support Planning following an episode of deterioration or carer struggling to cope resulting in a hospital admission. Once a person has settled into a new care home, planning discussions can be effective.

Advance Care Planning for people with advanced serious illness and end of life care needs is associated with improved patient experience and reduced hospital admissions. Compassionate and honest communication is fundamental to helping people to make decisions about end of life care through these planning discussions. This process should include a consistent approach to identifying, recording, flagging, sharing and meeting the information and communication support needs of patients, service users, carers and parents with a disability, impairment or sensory loss.4

Discussions should ideally be fluid and progress over time, at a person’s pace, rather than as a single event. It may be that some patients do not want to have these discussions and this should not be forced. Patients may change their mind, so offering patients the opportunity to review and continue discussions about their goals of care is beneficial.

Task

Think about a specific patient who has died and who was or could have been identified prior to death - that is, had a known advanced serious illness and ‘expected death’. Did they have a care plan with these discussions coded and documented? Components to consider:

- Treatment escalation plan

- Advance Care Plan

- Mapping who is available to support the patient and family/carer in a crisis

See examples above and Example: Your Health and Wellbeing code mapping (XLSX file, 51 KB).

Discuss the following questions as a group (and someone take notes on the key points)

- Look for a patient that did not have any components of a care plan (TEP, ACP, Support Map), what opportunities were there to offer and have these care planning discussions?

- What could have been the benefits to the patient (+/- relevant family/carers), the practice, the wider system?

- What gaps were there?

- What would the practice do differently in future?

- How will the practice monitor improvement?

- Look for a patient that did have a care plan with some or all components documented:

- Who was involved in these discussions?

- When was the patient identified to have an advanced serious illness? How long after this did the care planning start? How long after care planning discussions did the patient die? Were there opportunities to improve the timeliness of the process?

- Were details of people important to them recorded, e.g. family, carer, neighbour?

- Was it documented that the patient did or did not have any specific communication needs, e.g.cognitive impairments, hearing or sensory loss, English not their first language?

- What was the quality and impact of conversations recorded?

- Was the patient flagged as identified on ‘Supportive Care Register’?

- If recorded, did the care the patient received align with their wishes? If not, why was their variation?

- Was the patient offered a copy of their care plan?

- Was the care plan information available to key professionals in and out of hours?

- What was done well and how could the care planning have been improved?

- How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

- Consider the processes involved in creating a personalised care and support plan?

- Clarify tasks undertaken by different members of the team when care planning (from diagnosis of an advanced serious illness to after death)

- Do all members of the team understand what information is to be included in personalised care and support plans?

- Does the practice have a robust, reliable template dataset to collect information about a person’s care planning discussions?

- Is this template dataset shared between other local practices/ CCG?

- Is the patient routinely offered a copy of their care plan?

- If relevant to your locality, do patients have online access to their care plans?

- Is the care plan information available to key professionals in and out of hours? e.g. via EPaCCS or hand held record

- How does the practice monitor improvement? How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

- Create a process map of PCSP5

- Start point of process map is identify patient.

- End point is patient having copy of plan.

- Use different coloured post- its, one for a step in the process, one for an area of improvement.

- Each stage needs to be broken down. The more detailed the better.

- The steps are placed sequentially horizontally.

- If one step can be done in several ways this is added vertically.

- Complete the process before adding the areas for improvement. These post-its are placed next or over the relevant step in the process.

- Once this is done participants may identify solutions and add it to the map using a different coloured post-it note.

Informing part of the evidence on Standard 5

- Objectives of PCSP agreed by practice team.

- Coding, Recording and Coordination system agreed by practice team.

- Personalised care and support plan available.

- Process map of PCSP.

QI 5: Continuous Improvement

The practice has identified areas for improvement from their process map (see 5.1b). They then use the three questions from the Model for Improvement, which are:

- What are we trying to accomplish?

- How will we know if a change has made an improvement?

- What changes can we make that will result in an improvement? One of these changes at a time are taken into a Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle.

References

- Mullick A. Martin K. Sallnow L. An introduction to advance care planning in practice BMJ 2013; 347:f6064

- Personalised care and support planning handbook

- NHS England: The journey to person-centred care

- Core Information NHS England, Long Term Conditions, Older People & End of Life Care

- Dementia Good Care Planning guide - NHS England

- Accessible Information Standard: Making Health and Social Care Information Accessible

- Quality Improvement for General Practice

Record: Those attended, apologies, and date of meeting.

The aim

For the practice to consider how the Five Priorities of Care during the last days of life are regularly assessed, reviewed and met to improve care for all people with expected deaths (i.e. known to have an advanced serious illness or frailty and on the practice 'Supportive Care Register').Principles

Prompts for Practice2

- Recognise: The possibility that a person may die within the next few days or hours is recognised and communicated clearly, decisions made and actions taken in accordance with the person’s needs and wishes, and these are regularly reviewed and decisions revised accordingly. Always consider reversible causes, e.g. infection, dehydration, hypercalcaemia, etc.

- Communicate: Sensitive communication takes place between staff and the dying person, and those identified as important to them.

- Involve: The dying person, and those identified as important to them, are involved in decisions about treatment and care to the extent that the dying person wants.

- Support: The needs of families and others identified as important to the dying person are actively explored, respected and met as far as possible.

- Plan and do: An individual plan of care, which includes food and drink, symptom control and psychological, social and spiritual support, is agreed, coordinated and delivered with compassion.

It is helpful to note NICE guidance care of dying adults in the last days of life (NG31).3 Or read the RCGP and Marie Curie top tips based on NICE Guidance NG31 (PDF file, 255 KB)4.

Discussion

In 2013, the Independent Review of the Liverpool Care Pathway panel published its report. In response, 21 national organisations came together to form the Leadership Alliance for the Care of Dying People. The purpose of the Alliance was to take collective action to secure improvements in the consistency of care given in England. The Five Priorities of Care for the Dying Person set out the approach to caring for dying people across all settings, to ensure high quality, consistent care for people in the last few days and hours of life.1 There are associated duties and responsibilities of health and care professionals.2

The priorities for care reinforce that the focus for care in the last few days and hours of life must be the person who is dying. These priorities are all equally important to achieving good care in the last days and hours of life. Each one supports the primary principle that individual care must be provided according to the needs and wishes of the dying person. To this end the priorities are set out in sequential order. The priorities are that, when it is thought that a person may die within the next few days or hours of life:- Priority 1: this possibility is recognised and communicated clearly, decisions made, and actions taken in accordance with the person's needs and wishes, and these are regularly reviewed, and decisions revised accordingly

- Priority 2: sensitive communication takes place between staff and the dying person, and those identified as important to them

- Priority 3: the dying person, and those identified as important to them, are involved in decisions about treatment and care to the extent that the dying person wants

- Priority 4: the needs of families and others identified as important to the dying person are actively explored, respected and met as far as possible

- Priority 5: an individual plan of care, which includes food and drink, symptom control and psychological, social, and spiritual support, is agreed, coordinated and delivered with compassion

This document deals specifically with the priorities for care when a person is imminently dying, i.e. death is expected within a few hours or very few days. However, it should be noted that, for people living with life-limiting illness, the general principles of good palliative and end of life care (reflected in the Duties and Responsibilities) apply from a much earlier point. Advance care planning, symptom control, rehabilitation to maximise social participation, and emotional and spiritual support are all important in helping any individual to live well until they die.2

The Duties and Responsibilities relate to care and treatment decisions made when a person has capacity to decide and when someone lacks capacity to make a particular decision. Anyone who works with or cares for an adult who lacks capacity to make a decision must comply with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 when making decisions or acting for that person.2Task

- Consider a sample, for example, the last 5-10 patients, who have had an expected death (that is, known to have ASI, EOLC or Frailty needs)

- Was the person identified on the practice 'Supportive Care Register'?

- Timeline between diagnosis with Advanced Serious Illness or Frailty; Identification of patient and carer/those important to them; being place on the practice 'Supportive Care Register'; gain PCSP; review at MDT; death; care after death assessment?

- Did they have 3 components of PCSP: TEP/ACP/Support Map (see Standard 6)? How did this impact their care?

- Which of the Five Priorities of Care were met? How? Are there any opportunities for learning?

- Which of the Five Priorities of Care were unmet? Why? Are there any opportunities for learning?

- Did you receive patient and/or carer feedback (See Standard 8)?

- How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

- How will lessons learned be shared with you GP networks and wider system?

- Consider patients on your 'Supportive Care Register'. Reflect on IF and HOW the Five Priorities of Care are met. Include in the team discussion:

- Does the practice routinely agree the lead clinician(s), accountable for the overall care?

- How does this lead clinician become known to the patient and those important to them?

- How does the practice prioritise patients to receive urgent access during routine and out of hours?

- What processes are in place to ensure each of the Five Priorities of Care are met for patients in the last days and hours of life, and those important to them? For example, include access to end of life anticipatory medication, syringe pumps; access to specialist palliative care.

- Do you receive patient and/or carer feedback? (See example, Standard 8).

- How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

- How will lessons learned be shared with you GP networks and wider system?

Informing part of the evidence on Standard 6

- People with Advanced Serious Illness, Frailty and EOLC needs are timely identified prior to an expected death Five Priorities of Care are met Audit criteria shared and agreed.

QI 6: Continuous Improvement

Audit implementation of 5 priorities of care across all deaths and action taken where outcomes achieved do not meet the practice accepted standards. Continuous monitoring of these criteria e.g. pain and symptoms assessed regularly in last days of life. For example, consider if the practice has a reliable system in place to assess with the patient and those important to them the 5 priorities of care AND document that the 5 priorities of care have been met, where possible.

References

- One Chance to get it Right: Priorities for Care of the Dying Person Published June 2014

- Priorities of Care for the Dying Person: Duties and responsibilities of health and care professionals Published June 2014 by Leadership Alliance for the Care of Dying People

- NICE guideline [NG31] Care of dying adults in the last days of life Published December 2015

- RCGP and Marie Curie top tips based on NICE Guidance NG31 (PDF file, 255 KB)

Record: Those attended, apologies, and date of meeting.

The aim

- For each staff member to tap into their own experiences of handling patients and carers affected by anticipatory grief (patient and carer) and bereavement (carer).

- For staff to have a shared understanding of how best to support anticipatory grief and bereavement – considering medical and de-medicalised (non-health) support.

- To consider how the practice can robustly identify the minority of people who may require intervention. (this starts at having a concise, accessible, timely record of deceased patients and their bereaved).

Principles

- Recognise and acknowledge anticipatory grief and bereavement needs of patients and carers.

- Assess and advise on 'normal grief' and more complex grief.

Discussion

Due to the family medicine nature, general practice regularly comes into contact with people who have anticipatory grief (whilst living) and also the bereaved at some point in their experience of grieving. This can be an extremely satisfying aspect of general practice and an important part of building the continuity of care within the GP-patient relationship. Most bereavement reactions are not complicated and the necessary support is provided by family, friends, and various societal resources. It is important not to 'medicalise' normal grief. Therefore, it is helpful to understand the normal process of grief and what can be expected in order to then understand more complicated grief and the associated risks. Loss is completely personal and many events can result in grief, for example, death of a spouse, family member or friend; child loss; miscarriage and stillbirth; loss of an ability (such as hearing, sight, physical ability) and even pet death. Loss can be recognised by all members of the practice team and everyone in the practice can have/develop a role to support people in some way. Typically, GPs and District Nurses use home visits, telephone consultations, and condolence letters to support bereaved people1.

Task

Each person to think about a specific patient or carer you have handled who was/is affected by anticipatory grief or bereavement:

- Patient 1 with 'normal grief'.

- Patient 2 'requiring more medicalised intervention(s)'.

- Go round the group and ask people to say which patient they are thinking of. Depending on time, agree one or two patients to discuss in more detail.

- Ask if people are willing to volunteer A FEW WORDS ONLY what was most rewarding about being involved in their care.

- Ask what people found challenging? Are staff left with effects of professional grief?

- Discuss the following questions as a group (and someone take notes on the key points):

- How do practice staff think they should care for patients who are bereaved?

- Is there a system in place to for all staff to access a timely record of deceased patients and their bereaved?

- How does the practice acknowledge a person has had a bereavement?

- Does the practice routinely offer any signposting support?

- Using examples, how did the patient experiencing anticipatory grief or bereavement present/ get noticed by different staff? First for patient 1, then repeat for patient 2.

- Who had contact (any form) with the patient?

- Were there other opportunities for identifying their grief needs?

- What were their needs – health, psychosocial, cultural, spiritual, practical and other?

- Explore different people's attitudes, beliefs and experiences.

- What worked well /made a difference? – for the patient, for staff, for the practice?

- Is there learning for i) staff, ii) the practice, iii) external to the practice.

- What will people do differently in the future.

- How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

- How will lessons learned be shared with you GP networks and wider system?

- Set a review date.

Informing part of the evidence on Standard 7

- Identify people with anticipatory grief and bereavement needs.

- Practice protocol of support offer, agreed by practice team.

- Audit criteria shared and agreed.

References

- Nagraj, S. & Barclay, S. (2011) Bereavement care in primary care: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. BJGP

QI 7: Continuous Improvement

Regular audit (XLSX file, 307 KB) of support offered to the bereaved, for example, documented contact with the bereaved, support information given.

Record: Those attended, apologies, and date of meeting.

The aim

- For each staff member to tap into their own feelings of what would be expected within the practice to actively support the practice team (clinical and non-clinical) in personal death, crisis, loss.

- To develop a robust practice system to collect patient and staff feedback.

- To develop and keep updated a system accessible by professionals and patients with a list of services and support groups in the local community.

Principle

- Create and embed a culture of compassion within the practice, felt by all staff, patients and those important to them.

- General Practice hubs linking compassionate health support with non-medical supportive networks within your local community.

Task

- Consider how the practice regularly collects, analyses and shows learning from staff experience.

- Does the practice routinely offer staff the opportunity and safe space to debrief and give feedback? i.e. the impact of handling crisis, dying, death and bereavement on staff members and to understand their experience of care provided.

- If yes, by what method, for example, informal, formal? How is this structured?

- How does practice leadership involve staff to help develop a supportive, caring environment for staff?

- How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

- Consider how the practice regularly collects, analyses and shows learning from patient and family/ carer experience to continue to improve the quality of care (See examples: Experience of care questionnaire (PDF file, 58 KB); Briefing notes on patient experience of care questionnaire (PDF file, 371 KB); commitment form (DOCX file, 48 KB); PEoC phase one report (PDF file, 266 KB).

- Does the practice routinely offer patients and carers/those important to them the opportunity to give feedback? i.e. to understand the care they received, services used, gaps in care and services, outcomes linked to their care plan etc.

- Does this include the last days and hours of life and care after death?

- If yes, by what method, for example, informal, formal? How is this structured? For example, routine survey (see example above)?

- How often does the practice sample to try and avoid bias and enable comparison year on year, for example, sent to a reviewed sample of XX carers and family members each year over September-November?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of different methods?

- How will lessons learned improve future practice? Is there an action plan?

- Is there a system available and accessible (online or information sheet) to professionals and patients with a list of services and support groups?

- What non-health support networks and groups and available locally?

- How does the practice promote these local supportive networks within the community?

- What works well? What are the gaps?

- How does the practice collaborate/ support development of peer-led and voluntary groups?

- How does the practice involve your Patient Participation Group and/or patient or carer champions for the practice?

- What opportunities are available to collaborate with your GP networks, CCG and wider health and non-health systems, for example, schools, places of worship, voluntary sector organisations etc?

Informing part of the evidence on Standard 8

- System to learn from patient and staff feedback

- List of services and support groups in the local community – accessible to professionals and patients

- Patient and Public involvement and leadership

- Action plan for improvement based on qualitative patient and staff feedback

QI 8: Continuous Improvement

In order that lessons can be learned from the experience of advanced serious illness, EOLC, caring responsibilities, death and bereavement. Lessons can be shared with the relevant people.

Consider practice staff/ patients/ carers feedback and how the practice is meeting the end of life/ bereavement care needs, and show how any information provided is used to help improve care and support by achieving:- 2-5 family/care-giver or patient interviews e.g. semi-structured discussion, using an agreed template or annual carer survey relevant to EOLC needs.

- Staff feedback to support the QI planning e.g. survey, debriefs, SEAs

- MDT feedback to support the QI planning e.g. survey, discussion at MDT

- Annual evaluation of compassionate organisational culture

Resources

- Palliative care reimagined: a needed shift

- Useful resources for Wales palliative care: Palliative Care Wales, NHS Wales

Multi-professional mini-modules

- ‘Practical steps to assessing your baseline and developing a compassionate workplace culture and leadership in general practice (0.5 CPD points)’

- Podcast, ‘Developing a compassionate workplace culture and leadership in general practice – learning from a GP pilot site (0.5 CPD points)

- Awareness of national resources for instance from Compassionate Cymru

End of life care

General practice, alongside primary and community services teams, plays a key role in the delivery of care to people, and those important to them, affected by advanced serious illness and end of life care. This is a clinical priority area for the RCGP. The College encourages GPs and primary teams to regularly keep up to date on end of life care, depending on their role and relevant learning needs. General practice service development plans should consider how practices continuously improve the provision of end of life care, both directly and in collaboration with the wider system.

In 2019-2020, end of life care featured as a quality improvement module in the Quality and Outcomes Framework in England. Macmillan and the North West Clinical Network have developed a series of multi-professional blended learning resources. This has been in partnership with NHS England, and the RCGP and Marie Curie partnership. These resources support learning and best-practice end of life care quality improvement in your practice.

These modular education resources are free to access, simple to use and provide useful and meaningful continuous professional development (CPD). The resources can be used over coffee, with colleagues or as part of teaching. They can also be used by, and with, colleagues beyond primary care.

The resources also support the RCGP and Marie Curie Daffodil Standards – the UK General Practice Standards for Advanced Serious Illness and End of Life Care. The Standards have been designed by GPs and experts to offer a structure for practices, whatever the starting level, to have a clear strategy to consistently deliver the best care to all people affected by terminal illness. Further information is contained within the RCGP End of Life Care toolkit. Please make use of this resource as personal CPD, teaching aids as well as to help enable service improvement within your practice.

We would like to thank NHS England and NHS Improvement for commissioning the development of these resources to help support General Practice improve end of life care.

Animation film

This short video provides an overview of how to undertake a retrospective death audit and interpret an initial baseline audit. We recommend starting with essential CPD on 'Diagnose how your practice delivers EOLC and best-practice learning examples' plus the retrospective death audit below.

This masterclass is focused on Learning from your retrospective death audit in general practice. This masterclass equates to 0.5 CPD points. (Note: doing an audit of your last 20 deaths, using the RCGP template (XLSX file, 304 KB), will earn a further 1 CPD. Reflection on your audit and forming your practice quality improvement plan can earn additional 1-2 CPD points).

This masterclass is focused on identifying, assessing and supporting carers (up to 1.5 CPD points). Access a list of resources relevant to this masterclass (DOCX file, 23 KB).

- Module 1: Introduction - the context of caregiving: developing 'carer-awareness'

- Module 2: ‘Getting started’ – Practice processes for identifying carers in palliative and end of life care

- Module 3: Enabling practices to become ‘carer-ready’

- Module 4: Comprehensive, person-centred carer assessment and support

This is a set of four short videos to introduce the concepts around the benefits of early identification of patients reaching the end of life, how we may be able to improve our identification of such patients, why Advance Care planning is important, and an introduction to information sharing and mental capacity. These videos are brief resources that can be used by a professional for their individual learning or as part of a presentation or workshop.

- This video outlines some of the reasons identification of patients nearing the end of life is important.

- This video gives some tips and tools that can be used to identify patients nearing the end of life.

- This video gives an introduction to care planning for patients nearing the end of life.

- This video outlines some of the questions and challenges surrounding Mental Capacity and Data Sharing.

‘Courageous Conversations’ is a workshop designed to support primary care professionals to have conversations with people about cancer and other diseases, from diagnosis to discussions at the end of life.

The workshop resources encourage reflective practice and help participants to consider barriers and facilitators to challenging conversations.

Comprehensive resources include video consultations, facilitation information and scenarios for skills practice. They should be used as a full suite of interrelated resources and are not intended for separate use. They should also be delivered by colleagues who have attended one of Macmillan’s ‘train the trainer’ workshops.The link will take you to the Macmillan ‘Support for primary care’ page and if you scroll down the list of resources, ‘Courageous Conversations’ is the sixth tab down.

Macmillan Cancer Support - Courageous Conversations primary care training workshop.

The masterclass is designed to be delivered by a facilitator as part of a study morning/ afternoon, the training consists of four lessons which are accompanied by facilitator notes (DOCX 30 KB).

- Lesson 1 (PPT file, 3.8 MB) provides clarity around what a PCSP is as well as how it fits in with other EoLC related tools.

- Lesson 2 (PPT file, 5.3 MB) demonstrates skills and behaviours which enable the process of PCSP to be initiated and conducted in a way that is person-centred and supportive of the person.

- Lessons 3 and 4 (PPT file, 5.3 MB) - Lesson 3 considers how to involve those close to the person in the process according to their wishes and lesson. Lesson 4 considers practice processes in terms of documenting, sharing and reviewing PCSP. We would envisage Lesson 3 and 4 being delivered at the same time.

If you have any queries about this masterclass please contact england.personalisedcare@nhs.net.

Multi-professional mini-modules

- Practical steps to assessing your baseline and developing a compassionate workplace culture and leadership in general practice (0.5 CPD points)

Note: doing a staff survey on EOLC experience and compassion in the workplace, using RCGP template, will earn a further 1 CPD. Reflection on your survey and forming your practice quality improvement plan can earn additional 1-2 CPD points.

- Communication and listening skills – An introduction, for receptionists, HCAs, administrators etc (10 minutes)

Multi-professional podcasts

- How to support family and carers in end of life (0.5 CPD points)

- Developing a compassionate workplace culture and leadership in general practice – learning from a GP pilot site (0.5 CPD points)

- NHS England and Improvement

- RCGP

- Marie Curie

- North West Clinical Network

- Macmillan

- Sage and Thyme

- Dr Catherine Millington-Sanders, RCGP and Marie Curie End of Life Care Clinical Champion

- Dr Joanna Bircher, RCGP QI Clinical Champion and Clinical Director of GM GP Excellence Programme

- Dr Dharini Shanmugabavan, RCGP Medical Director of Clinical Quality

- David Parker-Radford, RCGP Head of Clinical Quality and Improvement

- Rosie Alouat, RCGP Quality Improvement Project Manager

- Professor Gunn Grande, University of Manchester

- Dr Gail Ewing, University of Cambridge

- Dr Elizabeth Phillips, GP Partner, Springfield Surgery

- Michael Connolly, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust

- Dr Rachael Marchant, RCGP End of Life Care Clinical Support Fellow

- Jo Harvey, Personalised Care Group - NHS England and Improvement

- Dr Charles Campion-Smith, Macmillan GP Advisor (retired)

Useful documents and support

- Appendix A - Example Audit Data Set Template and SMART Goals (DOCX file, 69 KB)

- Appendix B - Daffodil Standards and QOF Retrospective Death Audit (XLS file, 305 KB)

- Appendix C - Example Daffodil Standards QI PLAN collection template (PDF file, 332 KB)

- Appendix D - Example Management Self Assessment Evidence Collection Template (XLS file, 78 KB)

- How to JiC QI Project leaflet (PDF file, 350 KB)

- Sudden Bereavement Support Pilot – supporting the sudden death of GPs and practice managers

Daffodil Standards for Primary Care Networks in England - achieving EOLC QOF (PDF file, 335 KB): This short guide gives a step-by-step approach, using the RCGP & Marie Curie Daffodil Standards General Practice quality improvement framework to support PCNs.

Working with Older People's Care Home population in your Primary Care Network, GP Clusters or Federation (PDF file, 438 KB): An ambition for a Primary Care Network, GP Cluster or Federation is to improve the care for their local populations. Older people in care homes are part of a practice, PCN, GP Cluster or Federation population, described in the core Daffodil Standards. However, there have been many requests from general practice for some simple tools to focus solely on the quality of care delivered by general practice to older people in care homes.

This Standard offers some guidance to PCNs, GP Clusters and Federations to reflect on and build ideas together of how to improve care delivered by general practice teams to older people in care homes.

Daffodil Standards Bitesize reflections guide notes (PDF file, 345 KB): Following requests for a simple tool that focuses solely on the quality of care delivered by general practice to older people in care homes, we have created this Good Reflections Guide.

This offers guidance to groupings of GP practices described differently across the UK as Primary Care Networks GP Clusters and Federations to enable them to reflect on current practice and in turn generate ideas together of how to improve care.

There is also a Daffodil Standard MDT / ward round template (XLS file, 307 KB) to collect and monitor your progress across your PCN, GP Cluster or Federation population.

Newsletters