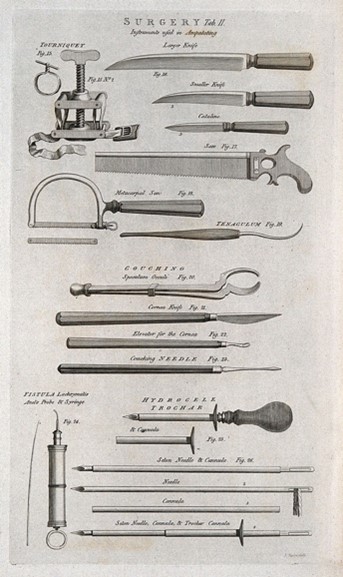

Banner image: surgical instruments, including a catheter, bistouries, needles and probes. Image credit: Wellcome Collection.

When discussing the day-to-day duties of a GP, routine tasks come to mind, such as prescribing medication, carrying out tests or discussing treatment options. A morning amputation followed by some apothecary work are less likely to make the list today. Yet such tasks would once have featured in a doctor’s day and influenced the tools in their bag.

The 1850s saw the start of general practice, and the next eight decades saw a shift as doctors became specialised. As education routes and boards of accreditation evolved, the role of the general practitioner and surgeon became defined and distinct. The Medical Act of 1858 laid down the minimum standard of medical education necessary for doctors. This set the path to specialisation and, even by 1892, William Osler recognised increasing specialisation:

The rapid increase of knowledge has made concentration of work a necessity; specialism is here and here to stay.

As time went on, the role of the GP became codified and respected as a medical counsellor to the patient and provider of general care, who could refer to the specialist when needed. As such, the tools that were once so key to the doctors duties - his surgery equipment and apothecary tools - became relegated to the museum shelf, acting as a material memory of these changes.

Listen to the collection

A GP's duties have changed over time, and different challenges have come and gone. Our oral histories recount these, from Maggie Eisner’s experience of delivering a baby during the World Cup to Ann Telesz's discussion of how home visits have changed more broadly.

- Maggie Eisner on delivering a baby in a house full of people watching a football match

- Ann Telesz discusses post-surgery care at home, and her experience in home births

Snapshots from the archive

These archive stories provide insight into how the daily routines for GPs have changed. From rural doctors forced to conduct their own x-rays and pathology without the assistance of hospitals, to wives enlisted into helping with minor surgeries, these stories demonstrate how much the duties of the GP have shifted over the years.

"In 1948, midwifery still played a prominent role in general practice. Antenatal clinics were often run by the local authority, but many GPs began to run their own. Deliveries were mainly domiciliary, with private patients treated in local nursing homes and only the most difficult cases allocated to hospitals. In my practice, we also had the privilege of GP hospital beds in our own NHS hospital. Here, deliveries were carried out by the mother's own GP: forceps delivery, breech delivery, everything up to caesarean section.

"Domiciliary delivery forged close links with the district midwives. The midwives, some of whom had recently been elevated to that status, were not always of the calibre of the younger trained midwife, but all led a busy and involved life in the community.

"I can remember on several occasions, carrying out a forceps delivery in the patient's home. Sometimes this would mean inducing the patient with chloroform, then whilst the midwife carried on with "the drops" going round to the other end of the bed to put on the forceps. On one notable occasion, having the great satisfaction, whilst in a basic cottage, performing a successful internal version and breech extraction. Postpartum haemorrhage was always a worry and the value of a manual removal of placenta quickly appreciated.

"In emergencies, the Flying Squad could be summoned from hospital. Domiciliary delivery produced a deep bonding between the doctor and the family was considered to be the bedrock of practice."

"We did minor surgery like suturing and cysts and our wives coped with casualties that came through the door. On one occasion, my wife coped with a man who had his legs run over by a bus. A truly splendid effort for a non-medical person.

"About once a month, we did our "operating list" on a Sunday morning. This was usually a circumcision, where we took it in turns to be the anaesthetist or the surgeon. The district nurse came too to do the dressing. Anaesthesia was ethyl chloride spray on an open mask and was very effective. We usually did two at least and then repaired to the nearest pub to knock back a pint before going our separate ways for lunch. We must have been pretty good, because I only remember two bleeds later in the day which were easily dealt with by a small stitch. Instruments were boiled in a saucepan. No bother at all.

"We did minor surgery like suturing and cysts and our wives coped with casualties that came through the door. On one occasion, my wife coped with a man who had his legs run over by a bus. A truly splendid effort for a non-medical person.

"About once a month, we did our "operating list" on a Sunday morning. This was usually a circumcision, where we took it in turns to be the anaesthetist or the surgeon. The district nurse came too to do the dressing. Anaesthesia was ethyl chloride spray on an open mask and was very effective. We usually did two at least and then repaired to the nearest pub to knock back a pint before going our separate ways for lunch. We must have been pretty good, because I only remember two bleeds later in the day which were easily dealt with by a small stitch. Instruments were boiled in a saucepan. No bother at all."

"I 'ran away to sea' and it was seven years before I re-surfaced with a wife, two children, a derelict house and what was left of a practice in a town from which nearly all the inhabitants had been evacuated. In accordance with pre-war tradition, I put up a plate describing myself as 'physician and surgeon' and this remained in situ for many years until a puzzled patient asked me why, with my qualifications, I could not personally remove the obstruction to his large bowel. It was not an unreasonable request since I was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, but I decided that I had better keep quiet about this in future and changed the plate to one describing me only as 'Dr', an unearned title which led to fewer complications."

"Anaesthetics and midwifery were much called on. Other GPs did part time work as surgeons. Or, say, ear nose and throat consultants, Patients were treated free. There were dozens of cottage hospitals, nursing homes etc (some less reputable than others were paying patients would be treated, usually by their own GP but a consultant might be called in. No doubt there were abuses, but it made for good relationships. Patents might have a minor operation at home, and most babies were delivered there. There were district nurses or private nurses who could be hired. After the NHS a GP had to choose either general or hospital practice, an unacceptable decision for many.

"In country areas the GP would have to do his own X-rays and pathology and tackle major surgery. Most GPs were able to do the limited range of pathology and bacteriology that was available. Satisfactory Public Health Laboratories had to wait for wartime. The Medical Officer of Health, often a GP, had a good deal of power."

Thank you for your feedback. Your response will help improve this page.