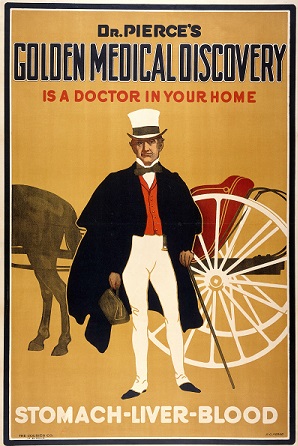

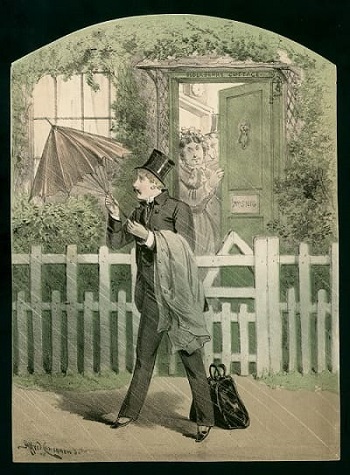

For generations, the doctor's bag was the symbol of the doctor’s profession. Its cultural legacy is seen in toy shops everywhere, in the toy doctor's bags we played with as children which made us believe that someday we might be doctors. It often marked a new chapter in the working life of a GP, given as a graduation present or presented at a doctor’s first surgery. Nowadays, it's less present in the modern imagination, but it still lives on in the nickname of the Gladstone bag, often called ‘the doctor’s bag’.

The bag and its tools are much more than simple symbols. While routines and practices have changed over the years, the bag has kept pace with these changes. These instruments are a material legacy of how the GP’s work has changed over time. How have the surgery instruments of the 1880s changed, and given way to the prescription pads of the 1980s? With these tools, we can find the challenges GPs have faced, from travel to global pandemics. It is these stories that this exhibition hopes to show.

Finally, this exhibition looks at what challenges await doctors in the future, and what is to come for GP practice.

Snapshots from the archives

Throughout the archives we have stories of the challenges and triumphs doctors faced, often with their bag in hand. This exhibition features a handful of those stories from across the UK, from the late nineteenth century to the mid twentieth century.

These represent only a sliver of the experiences of GPs, one period in one region of the world. If you have memories or materials to share we would love to hear from you, so please contact us.

"I was born in 1924 and so was not in practice myself before the NHS. But my father was a GP in Brighouse, in the industrial West Riding of Yorkshire. He talked to me a good deal about his patients and his anxieties, and I spent a lot of time going visiting with him. I have some very clear impressions of that time, the '30s, a time of distress and unemployment for working people…

"There was not much sophisticated technology. They had stethoscopes, auriscopes, proctoscopes, catheters (metal), syringes (glass and metal) and a ferocious armoury of midwifery implements. A range of surgical instruments, as most GPs did quite complicated surgery, usually in the patient's home. But my father and his partners had a well-equipped operating room at the surgery. They were very skilled diagnosticians and operators, and (without antibiotics) knew all about sterile techniques. Although, wounds often had to be drained and secondary closure was usual for contaminated injuries…

"There was a lot of home visiting. Hardly anyone had a car, and I used to come round with him. It enabled me to escape my mother's social activities and bury my nose in a book. I think he enjoyed having someone to talk to, and I would often come into houses with him, so discovering at first hand the realities of bringing up a family on thirty shillings a week, without any kind of modern amenities. He felt it was a great privilege to walk in and out of people's homes as a welcome visitor, and when I in my turn did the same, I felt it too. But this has gone."

"Instruments such as ophthalmoscopes, specula and so on were non-existent in the practice. I was fortunate in that my senior medical officer had let me keep a few army items. In addition, I had been fortunate enough to be given his kit by a captured German medical officer. Needless to say, like most items of military equipment, the German version was far superior to anything we had. I used most of them till I retired, but still have their container. A tin trunk, cleverly designed, now housing woodwork tools!"

"I am reminded of the technology available for giving blood and intravenous fluids in 1948. These were no sterile, plastic, disposable packs. The 'giving set' arrived in a brown paper packet opened to provide two large steel needles and a length of red rubber tubing. These were then returned for re-sterilising. All fluids and blood were in bottles with rubber seals.

"Common diseases in general practice in 1948 were TB, appendicitis, measles, and scarlet fever, with rheumatic fever becoming more infrequently. Osteo was not uncommon. ECGs were not used in general practice as the machines were still too large, but the midwives were equipped with gas and air machines which were an improvement on rag and bottle chloroform at domiciliary deliveries. One problem at house deliveries in 1948 was the utility bed' introduced when wood was scarce. It stood about 10 inches off the ground, and stitching a peri had to be done sitting cross-legged on the floor."

"Rotas for 'off-duty' did not exist. When you went to the theatre or the cinema, you gave your name at the box office and the attendant made a note of where you were sitting. Every time she walked down the aisle you sat tensely waiting to see if it was you she was after.

"Alternatively, there might suddenly appear on the screen, superimposed on the handsome features of Clark Gable, the news that you were required elsewhere and you had to leave your wife to tell you later if the hero got the girl in the end. Once at a first division football match I watched a board being carried right around the field invoking a fair amount of laughter and rude comment. When it finally faced my way I read that I was wanted at the surgery after the match. It was only half time and the crowd was not impressed by the priority given to my seeing the second half against attendance to whatever was required at headquarters."

A place for everything

Many of the doctor's bag core requirements are the same across the world, from protective equipment like masks and gloves to diagnostic equipment like stethoscopes, ophthalmoscopes and sphygmomanometers. Paperwork and the correct stationery remain crucial in ensuring patients are correctly treated.

However, regional variations can appear, with different areas facing their own challenges. Language barriers often present a challenge to doctors working with varied communities. Having leaflets which are translated into the patient’s own language can help bridge this gap. To understand more about the importance of indigenous languages in health communication, read how one project sought to overcome language barriers in Tenango, rural Mexico.

Elsewhere, the landscape itself can provide its own challenges, such as the cold of the North American climate. When writing his advice to Canadian colleagues on how to stock their bag in 1980, Dr Sheldon highlighted how the icy winters were liable to freeze ampoules. A doctor needed to be prepared to thaw them out, with distilled water held in his coat pocket and torch to check it had defrosted. Meanwhile, other challenges in cold climates could be less medical, as Dr Baines found when working in rural Alaska. Here, Dr Baines might travel days to reach a village, and could be cut off entirely. In situations like these, a change of clothes, a flannel sheet and a good book could all be essential to the doctor's bag. Find out more about Dr Baines' experience working in rural Alaska.

Contact us

These are just some of the stories from the RCGP archive and collections. If you have memories or materials to share we would love to hear from you. Please contact: heritage@rcgp.org.uk

Acknowledgements

- Curatorial team: Freya Purcell, Heather Heath, Lindy Tweten, Preksha Kothari, and Philip Milnes-Smith

- Design and installation: Aura Creative

- Digital support: Laura Comben, Priya Dodhia, Sami Pratt, and Swéta Rana

- With thanks to: Clare Gerada, Stephen Young, Jodie Green, Jenny Lebus, Ian Jutting, Amanda Howe, Jean Seymour, Selina Gellert, Ruth Bishop, and the Rural Forum

Thank you for your feedback. Your response will help improve this page.