If there is one word to sum up the healthcare needs of people in prison, it is “complexity”, explains Dr Caroline Watson chair of the RCGP Secure Environments Group (SEG). Alongside every health complaint you can think of – often greatly exacerbated by health inequalities – the patients she sees in her role as a GP at a Category B prison in Bedfordshire also frequently have complicated substance misuse and mental health challenges.

It is a group of patients who are more likely than the general population to be carrying childhood trauma and have undiagnosed neurodiverse conditions. Many report previous poor care experiences or have struggled to access community-based health services. Once in prison, access to external care can also be difficult.

Dr Watson finds the work incredibly fulfilling, describing parallels with homeless patients at a GP practice she worked at previously: “There is a great honesty with people in prison, there’s no pretence, and often we’re seeing the same patients coming back in again. That’s what the homeless practice really taught me: that you accept the person when they fall flat once, twice, three times. People automatically feel judged before they've even walked through the door, so it's about saying, ‘you're welcome’, and to keep trying to engage.”

There may not always be much external sympathy for providing good healthcare to those in prison, but stark health inequalities will still be there when someone is back in the community, so it’s a real opportunity to address those when someone is in prison, she says. “They need to be able to contribute to society, and so actually attending to their health needs is going to be of value to everybody in the end.”

The GP is the person who is able to provide the overview and to connect the parts within a much wider prison healthcare team. The ability of the GP to “hold the risk” is key, when patients are coming into prison withdrawing from a complex cocktail of drugs or where mental health, substance misuse and healthcare issues, including chronic and infectious disease all intertwine, she notes. As is the ability to be a creative problem solver.

“We’ve provided patient care and supported the wider health team to manage people living with limb amputations, late complications of diabetes, terminal illnesses, those waiting for organ transplants – there is nothing that stops somebody coming to prison from a health perspective.”

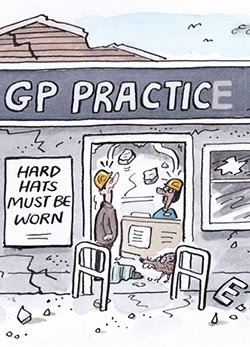

An ageing prisoner population is also making healthcare more complex, yet despite a clear role for the GP, there is a real risk that it will be sidelined as budgets are squeezed ever further, Dr Watson observes?

“We are seeing nurses being given more risk to hold without adequate senior clinical support, as fewer GP sessions are offered in prisons due to financial restrictions. It risks reducing the GP role to an occasional visiting service, losing the broad and central role of the GP in providing patient care, continuity of care and clinical leadership within the multi-disciplinary healthcare team.”

Since taking over the chair of the SEG in 2022, Dr Watson’s vision has been for the group to provide UK-wide strategic clinical leadership within the justice system, to support high standards of clinical care through education, research and policy development, and to forge stronger inter-professional links, including with the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of Nursing.

The SEG has a wide-ranging programme of work, consistent with the breadth of health issues experienced by patients. Members have set up a popular e-learning hub, input into the safer prescribing agenda by co-authoring two editions of ‘Safer Prescribing in Prisons’, advised on national committees, delivered training to support complex pain management in prisons, and are developing new inter-professional resources to support people with pain in contact with the justice system both in prison and in the community. The group also contributes to the health inequalities agenda at a regional level and nationally through the Core20Plus5 Ambassador programme.

Dr Watson’s vision for interprofessional collaboration is bearing fruit through a formal joining of royal colleges for shared work, under the name of Health and Justice UK, which has its own website hosting a raft of resources. It now organises the highly-successful annual Health and Justice Summit. Its latest project is to develop and grow ‘communities of practice’ that reach across different regions and specialist areas, including children and young people, women, immigration removal centres and secure hospitals. The hope is that these communities will provide interprofessional learning, opportunities to share good practice, and networks of support.

If you are interested in finding out more about the RCGP SEG and providing care to people in contact with the justice system, please contact seg@rcgp.org.uk.

Read more

Thank you for your feedback. Your response will help improve this page.