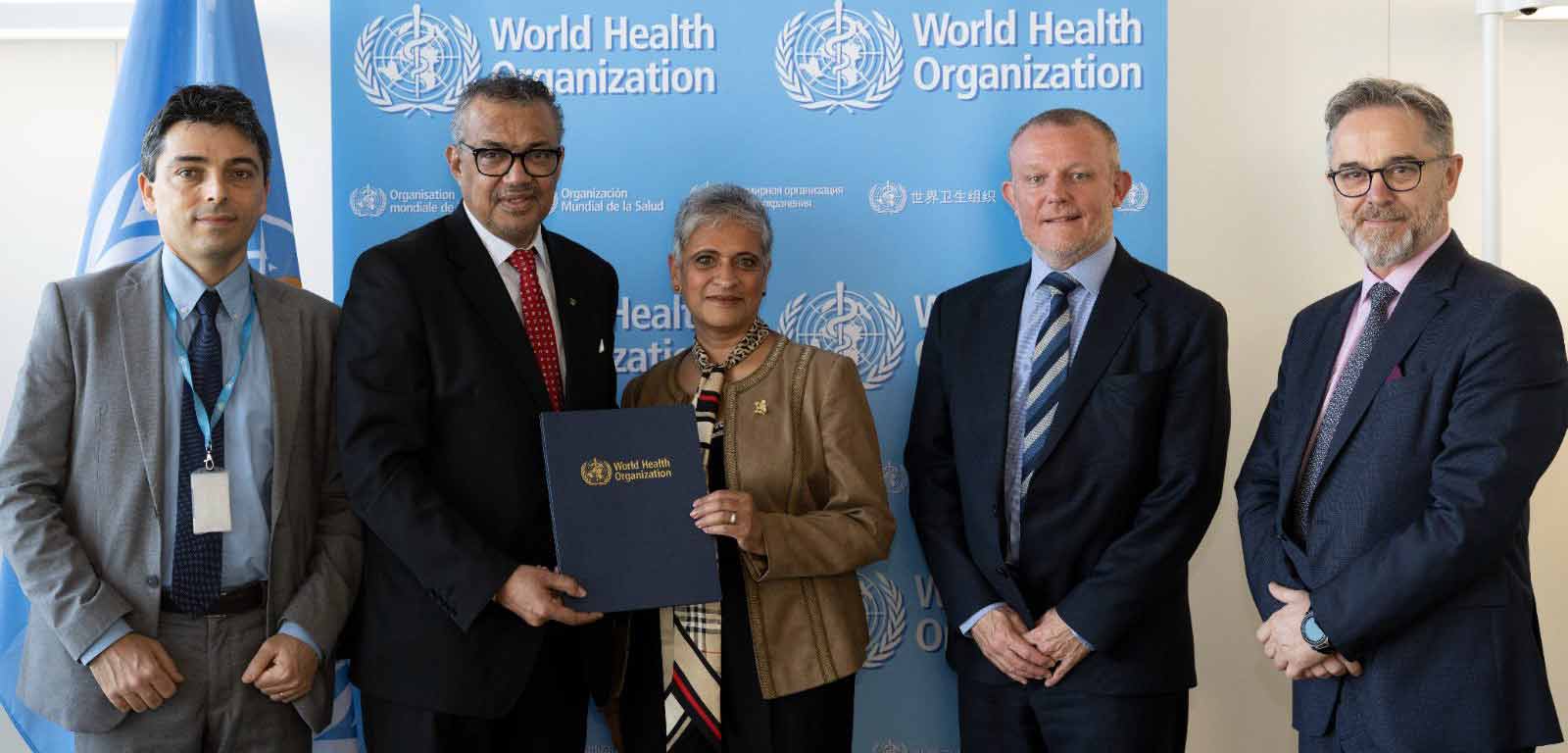

In early April, RCGP Chair Prof Kamila Hawthorne travelled to Geneva, home of the World Health Organization to meet Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, its Director General.

She went to renew a Memorandum of Understanding, first signed in 2019 by then Chair, Prof Dame Helen Stokes-Lampard. It commits to working with the WHO to address workforce barriers to achieving one of the organisation’s key goals: ensuring universal healthcare.

Signing such an agreement with the WHO is a considerable achievement as they are usually reserved for national governments, not individual organisations. The RCGP's commitment to not only raising the standards of primary healthcare in the UK, but globally. Its experience at delivering educational programmes abroad to promote primary healthcare sets the college apart.

Since 2019, when the MOU was first signed, the Covid pandemic stalled any meaningful progress with the partnership being made, but Kamila is keen to get the ball rolling again.

“A strong primary healthcare system is key to a sustainable, successful healthcare system generally. The evidence showing that is clear. Despite the immense pressures we’re facing in general practice in the UK, the model itself is not broken and it is one to be proud of, and we’re keen to support the development of stronger primary care globally,” she says.

First steps will involve coming up with a comprehensive work plan with the WHO and then moving on to implement it. Whilst details of what this will look like are to be decided. The College’s role is likely to be in supporting primary care medicine education. Especially for general practitioners and family doctors working in rural areas in low and lower-middle income countries.

Kamila’s visit coincided with the 5th Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, and she was struck by the scale of the workforce crisis in health and care worldwide.

“We have serious workforce shortages in the UK, but we are not alone – globally, we will likely be short of 10m healthcare workers by 2030; and there are high levels of burnout amongst health and care workers in all countries,” she reflects, “2030 is only seven years away, so this issue is urgent."

She also noted that whilst women make up two thirds of the health and care workforce. There is an overall gender pay gap of 24%, and only a quarter of medical leadership positions globally are filled by women.

Global workforce shortages have clear implications for the UK, Kamila says. “We heard how some low-income countries, for example Ethiopia and Kenya, are graduating double or treble the number of medical graduates than previously, but the ‘brain drain’ to high-income countries means they are still struggling.

“Decision makers often jump straight to overseas recruitment as a way to address domestic workforce issues, especially in the short term, but we need to think ethically about how this impacts on other countries. We all have a responsibility to work together to make our global healthcare workforce as equitable as possible.”

Around 3,000 delegates representing 140 countries attended the conference. Either in person or virtually, to share experiences and ideas. One scheme that caught Kamila’s attention was a partnership between Sudan. A country in which around 60% of doctors emigrate. The Republic of Ireland, whereby experienced Sudanese family doctors go to Ireland for a two-year postgraduate training placement and then return home.

“It works because it’s supported at Government-level,” says Kamila, “and strong support networks have been built amongst the Sudanese doctor diaspora. Ireland benefits from a boost in workforce, and Sudan benefits from doctors returning with two years of postgraduate training – it’s a win-win. Interestingly, though, the scheme doesn’t include primary care, and I think something along these lines would be worth exploring in the UK.”

Read more

Thank you for your feedback. Your response will help improve this page.