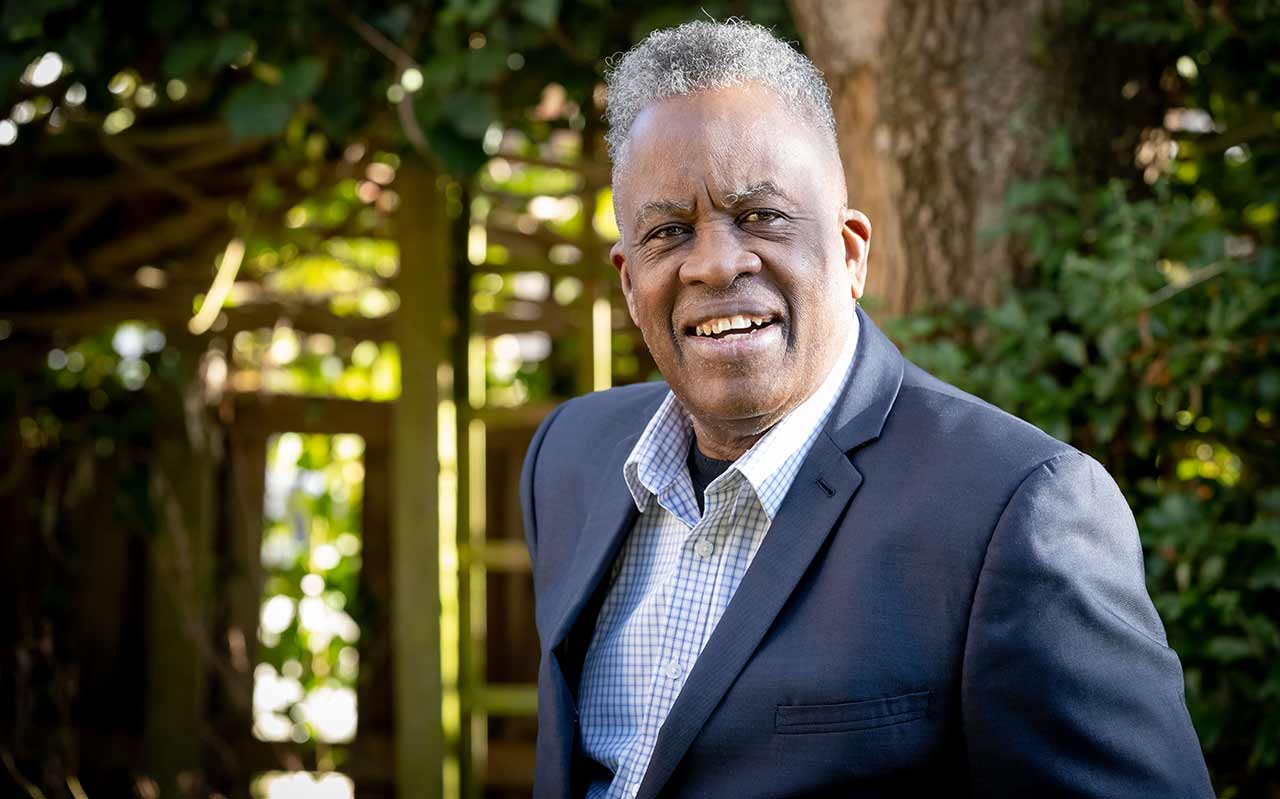

“The fund aims to help people get back on their feet so they can return to general practice,” he explains. It can be a lifeline, and their ultimate goal is to help a beneficiary resume their medical career, having been supported through their difficulties. “When it happens that is brilliant.”

This Christmas through their annual appeal they will be reminding GPs who are able to contribute how vital that donation can be. With the number of applications increasing, funding has also reduced, likely as a result of the cost of living crisis. The trustees who meet three times a year have had to review their criteria for applications in order to ensure sustainability for the future.

“There are a whole range of reasons people can suddenly find themselves in distress or in trouble and that is when they can apply to us,” he says. “We just need to remind everyone that there is a fund dedicated to this that they can support.”

In addition to his work with the Cameron Fund, Dr John also previously chaired the BMA Refugee Doctors Liaison Group – one of many long held positions at the BMA, including being a member of the BMA GPs committee – the goal of which is to support refugee doctors trying to enter the UK’s healthcare system.

“It’s a terrible waste,” he says of the highly qualified doctors unable to practise due to the complexity of navigating the systems to become licensed and registered with the General Medical Council. “It's not easy at all to do that, and so they are sitting around doing nothing, perhaps getting a job working as a delivery driver or whatever, so we work together with various other charities in the UK to try and help these doctors.”

This help involves access to resources like BMA library membership and counselling services. “We have doctors who are trained and willing to work, yet we’re not using them. Our goal is to make it easier for them to get into the system.