For the first generation of qualified women doctors in the late 1800s, hospital work was inaccessible without the required experience, which relied on an existing male network. With fewer barriers to entry, and particular focus on women’s and children’s health, general practice was therefore an acceptable and rewarding role.

Building on the historical role of women as community healers, general practice has typically allowed more flexible working to fit with other caring responsibilities and family life. Whilst often cited as attractive, this can play into patriarchal assumptions about women’s roles as carers as well as professionals.

“Women are neither physically nor morally qualified for many of the onerous, important, and confidential duties of the general practitioner” The Lancet, 1873

“The rough and tumble … of general practice makes it much less suitable as a rule for women than for men.” Sir Walter Fletcher, Secretary of the Medical Research Council, 1926

“No sphere of work in which women were more likely to come into their own.” Sir John Rose, PRCP, 1926

“Women in medicine are not fighting a battle of the sexes, but for the health of our professional body and for the health of patients. We are not prepared to go on as second among equals.” Lotte Newman, 1991

Key dates

1881 there were 25 registered women doctors in England and Wales

1917 Medical Women’s Federation (MWF) founded

1963 9% of GPs in England were women

2020 a 35% pay gap remained between women and men GPs

People

Find out more about individual women’s experiences by clicking to expand.

Elizabeth Garrett (1836-1917) was the first woman to qualify as a doctor in Great Britain. Inspired by Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910), the first woman to qualify in the United States, Garrett persevered tirelessly to become a doctor. British medical schools did not accept women, so Garrett combined private unofficial study, attending lectures at different institutions, and clinical practice at the Middlesex Hospital. To join the Medical Register, she eventually turned to the Society of Apothecaries, whose charter did not explicitly exclude women from their licensing exam.

The Apothecaries tried to deny Garrett’s eligibility, but legally they had to admit her. She passed on 28 September 1865, but the Apothecaries then reworded their charter to exclude women for a further 23 years.

Dr Garrett initially opened her own practice, followed by St Mary’s Dispensary for Women and Children in 1866. In 1870, she achieved a medical degree at the University of Sorbonne in Paris. She became a member of the British Medical Association in 1873, and remained its only woman member until 1892. In 1883, she was appointed dean of the London School of Medicine for Women, which had opened in 1874.

Dr Garrett Anderson was also an active member of the suffrage movement, and the first woman mayor in England, elected in Aldeburgh in 1908.

Image: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, photograph by Walery, published by Sampson Low & Co in February 1889.

June Pearson (1924-2011) qualified at Birmingham University in 1947 and married her fellow student Jim Davey the following year. As both a doctor herself and a GP’s wife, she played a variety of roles, typical for a medically-trained woman in these decades. Professionally she worked with her husband in his practice in Box, Wiltshire for 12 years. When Jim formed a partnership with local doctor Donald Taylor in 1958, June was a one-fifth partner. Later she developed a specialist interest in gynaecology and co-founded a family planning clinic in Bath in the early 1960s, becoming a trainer, before becoming a clinical assistant in genitourinary medicine at Bristol Royal Infirmary.

Surveys of women doctors carried out in these decades found that the most popular specialties were paediatrics, obstetrics, gynaecology, sexual health, marriage guidance and family planning, public health, geriatrics, psychiatry, and general practice.

June and Jim Davey had three daughters, and to enable both parents to continue working, two local women Olive and Margaret Currant fed the girls, put them to bed when needed, and provided meals for the family. Two daughters became doctors and the third a nurse.

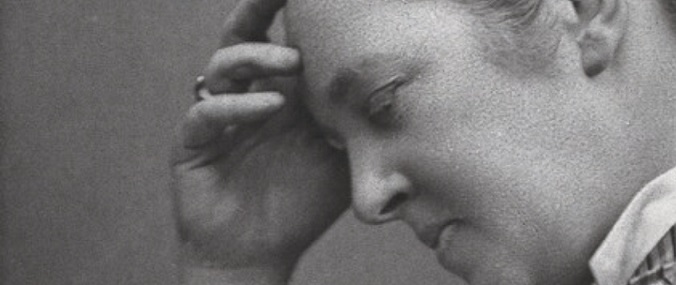

Image: June Pearson, while still a medical student in 1945.

Stories

A long tradition

This romanticised image of an elderly woman bandaging a younger woman’s hand represents the stereotypical role of a community healer in the centuries before medicine was regulated. Women have always provided healthcare, typically in an informal domestic role. As early as the 1100s, there is evidence of women terming themselves “doctors” in English legal documents, and in the 1600s, a small number were licensed to practice medicine by the Church of England.

Image: The Village Doctress, James Walker mezzotint after James Northcote, 1787. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

‘Boycotting the Lady’

In spring 1904, GP Dr Ethel Vernon (c.1876-1936) hit the newspaper headlines in Britain and America. Having served her probationary period as an attending officer at the Westminster Dispensary with a specific responsibility for women and children, the honorary consultant physician threatened to resign rather than work alongside a woman in a permanent appointment. In her place a male candidate with no relevant experience was appointed. The Star, an American newspaper, reported “It was frankly admitted that Dr Vernon’s qualifications were higher…that she was very popular with the rest of the staff and with the patients, and the Board of Governors came in for considerable criticism from medical men.”

Image; Western Times, 25 February 1904. Credit: Western Times, Exeter.

Voices

Listen to Dr Aaliya Goyal reflect on how cultural expectations for South Asian women have impacted on her career, and Gillian Craig discuss the difficulties finding work as a young unmarried doctor in the 1950s, with Amanda Howe.

Transcripts

Discover the exhibition

Find out more about the history of women in general practice by visiting our Women in GP exhibition.

Thank you for your feedback. Your response will help improve this page.